“The mutual-aid tendency in man has so remote an origin, and is so deeply interwoven with all the past evolution of the human race, that it has been maintained by mankind up to the present time, notwithstanding all vicissitudes of history.”

Peter Kropotkin Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution

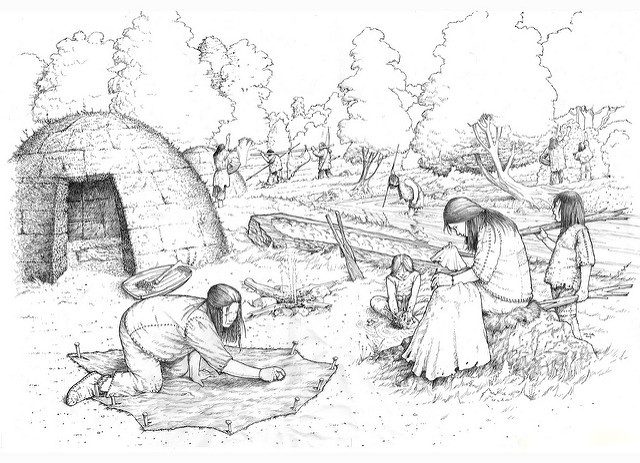

Anthropology typically credits our species’ success to our large brains and ability to make tools, but arguably our greatest survival strategy has been our ability to co-operate and work together.

The logic is simple. A lone individual in the wilderness can survive for a time, but the slightest injury or illness, and that individual will quickly succumb to the elements, starvation, or predators.

A family grouping offered better odds of survival, but with the addition of offspring, the duties and responsibilities of the founding pair bond are increased and their resources stretched, and, as with all defenses that are stretched, they become more vulnerable to the same dangers as a lone individual.

The first and most effective survival

strategy for our species was the formation of tribal groups. Such groupings

pooled their resources, to help insure nourishment, shelter, and defense

against predators. A few writers have postulated that the human brain is

hard-wired towards tribalism due to its evolutionary advantages.[1]

Tribes

Tribes were the first mutual aid societies.

The social structure of a tribe can vary greatly, but, due to the small size of customary tribes, social life involves a relatively undifferentiated role structure, with few significant political or economic distinctions between individuals.

Traditional tribal societies tend to have a Chief or Headman also known as the Big Man, but their authority was always subject to the approval of the rest of the tribe especially the tribal elders.

The ‘Big Man’ collected many of the resources from the tribe, but rather than keep it all for himself, a portion was stored so that it could be distributed to the tribe during times of drought, or if the hunt failed provide meat. He was also expected to redistribute those resources to feed work parties for village construction projects, hold numerous feasts and festivals where everyone would share in the food and which helped group bonding.

We can also see in the tribal structure the origins of government, and why government was a good idea. In this scenario, an authority figure who has earned the trust of the community oversees overseeing the collection and storage of surplus resources, such as grain, corn, smoked fish, honey etc.

Working in teams and communities is a force multiplier that, under normal conditions, produces surplus. This surplus is pooled in order to sustain the community during difficult conditions. Some of the surplus is used for projects that would benefit the community, such as digging wells, building fences for livestock, or walls for defense.

The tribal organization is often cited as an ideal system that validates such political systems as socialism and communism. However, as we shall see later in this chapter, such political systems have been a disaster.

The problem lies in the fact that the tribal system is not scalable. Just because a system works with a group of a hundred people, does not mean it will work with thousands, or millions of people.

There are three reasons a utopian tribal structure cannot work on a large scale. The first is trust. In a tribal society, members of the tribe choose leaders because they all know that person intimately. They have worked together, shared together and lived together. Their trust is based on firsthand knowledge. Their leaders have earned the trust of their fellow tribesmen.

In a nation state, most citizens would never have spent any time with, let alone even met in-person, their leaders. It would be impossible for citizens to develop trust and confidence in any political leader without direct experience. That so many do is a fault of our species that can perceive abstractions as reality. In a nation state we must base our trust in what such leaders say in public. Thus, such a system guarantees that all leaders will be liars at best, or more likely psychopaths.

Second, in a tribe, all members would have access to the ‘Head Man’ and council of elders, to ask for help, vent their grievances, or offer solutions.

In a nation state, it would be ludicrous to imagine that an ordinary citizen would be able to have a one-on-one talk with any political official. This means that it is unlikely, if not impossible, that a nation state would reflect the will of the people, and thus the people would have no influence on the way the state is run.

Finally, in a tribal society, should the leadership be incompetent, or making decisions that the tribe is in vast opposition to, they could remove their leaders from power in a day.

In a nation state, removing leaders is a long and drawn out process requiring years, assuming that the leaders would be willing to relinquish power in the first place. Thus, the damage such governments do cannot be prevented or remedied quickly.

This guide includes the best lessons gleaned from the study of tribal societies.

Similar to tribal organizations, the following community plans are based on undifferentiated roles with no hierarchy. Certain individuals will have a greater affinity and ability for fulfilling certain roles within the tribe, and their expertise may be deferred to in situations where decisions between the tribal members are at a stalemate. However, there is no hierarchy that must be obeyed.

In addition to kinship and extended family relations, another important factor to the formation of a tribe is shared values, customs, and ideology.

This is a crucial factor to social cohesion and any attempt at forming a community would need to ensure that members, if not sharing kinship, should at least share the same values and ideology. Indeed, shared ideology forms stronger bonds than kinship as anyone from a large family can tell you.

In times of social collapse, evolutionary instincts will drive people to form tribal association again for mutual survival. Those that cannot find a tribe to belong to, or find one too late, will find it much more difficult to survive.

A key advantage to forming a group for

mutual aid, is that should a major disaster occur, a group of people that

already have a social structure, mutual trust, and some training and equipment

will be better able to survive and take advantage of fleeting opportunities,

while other people are scrambling to survive themselves.

[1] Erich Fromm; Michael MacCoby (1970). Social Character in a Mexican Village. Transaction Publishers. pp. xi. ISBN 978-1-56000-876-7.